Disinfection byproducts are a class of contaminants that have been detected in drinking water throughout the country. Unlike things like arsenic and lead, most people are not familiar with disinfection byproducts. The goal of this article is to dive deep into the chemistry, history and policy surrounding disinfection byproducts.

What Are Disinfection Byproducts?

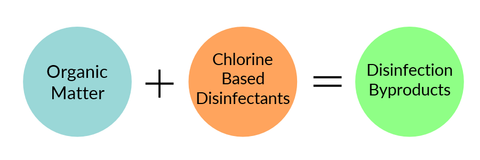

Water disinfection was an extremely successful public health accomplishment. It's the main reason why waterborne illnesses are not a persistent threat in United States tap water. However, adding chlorine-based disinfectants to water can have harmful unintended consequences, one of which being that they can react with other things found in tap water (e.g. organic matter) and form a class of halogenated chemicals known as "disinfection byproducts." Disinfection byproducts are generally regarded as an "emerging contaminant", because despite having identified more than 600 different disinfection byproducts, roughly 50% are still unaccounted for.

Why Do We Care About Disinfection Byproducts?

Many halogenated organic compounds are known carcinogens in humans (e.g. dioxin, DDT, Carbon Tetrachloride, PCBs), so they rightfully receive quite a bit of scrutiny when detected in tap water. While some disinfection byproducts in water have almost no toxicity, others have been associated with cancer, reproductive problems, and developmental issues in laboratory animals. Some population-scale epidemiology studies have also found an association between chlorinated tap water and these same problems in humans. Because more than 200 million people in the US use chlorinated tap water as the primary drinking water source, it’s something worth taking a very close look at.

How Are Disinfection Byproducts Regulated?

History Of Disinfection Byproduct Regulation

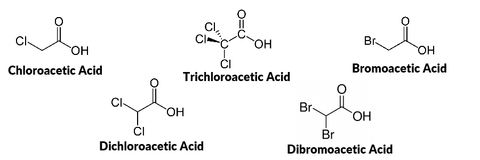

In 1974, trihalomethanes were detected in drinking water and linked to chlorine based disinfectants that were added to municipal tap water. Around the same time, the National Cancer Institute classified trihalomethanes as human carcinogens, and as a result, EPA established a drinking water standard for trihalomethanes in 1979. As more was learned about disinfection byproducts in water, the US EPA and other government, public health, and industry stakeholders began negotiating 2 stages of more comprehensive regulations in the mid-1990s. Stage 1, which was published in 1998 for 2002 compliance, ruled that haloacetic acids must also be monitored in tap water, in addition to trihalomethanes. The Stage 1 Rule also mandated that these chemicals be monitored throughout the entire water distribution system, not just a few predefined sampling locations. The results of the increased monitoring revealed that more municipalities were non-compliant than initially expected. Stage 2 of the regulation was published in 2006 (for 2012-2016 compliance), and further refined the sample collection strategy with the goal of protecting the public. In the future, most people expect that the regulations will continue to tighten as more about the long term effects of these chemicals becomes better understood, and the technologies that reduce their concentrations at the municipal level improve.

How To Know If A Municipality's Tap Water Has High Levels of Disinfection Byproducts

Overall, disinfectant byproduct concentrations are difficult to predict, because many factors influence their formation including: concentration of organic matter, chemical composition of the precursor materials, pH, temperature, type of disinfectant used, and the concentration of disinfectant. However, because monitoring for trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids are mandated by the EPA, the average concentrations found in the water supply must be made available to the public in annual drinking water reports.

Within a given municipal water system, different physical locations can have higher disinfection byproduct concentrations than others, based on where the home or business is located. This is because the longer it takes for the water to reach the home, the more opportunity there is for disinfection byproducts to form. Therefore, locations close to fast flowing water mains often have lower levels of disinfection byproducts than homes found at the periphery and low flow areas of the water distribution network. Additionally, disinfection byproduct concentrations can continue to rise in residential pipes/water tanks if the water remains stagnant for extended periods of time (e.g. during the work day, overnight). In fact, most municipalities recommend letting water run for 1-10 minutes before using it for drinking or cooking so pipes can flush out. (Obviously, nobody does this….)

What Are The Primary Ways That People Are Exposed To Disinfection Byproducts In The Home?

In the home, most people primarily use chlorinated tap water to drink, bathe, wash dishes, etc. A few studies have looked at the relative importance of the various exposure pathways, and found that showering contributed heavily to blood levels of trihalomethanes. While this may be initially surprising, it does make sense, because trihalomethanes can be volatilized in hot water and subsequently inhaled. During a shower, disinfection byproducts can also enter the body through absorption through the skin. Because most people come in contact with over 17 gallons of water in an “average” 8 minute shower, but drink less than a half-gallon of water each day, it makes sense that showering can be a major exposure path. Granted, this study only looked at the exposure route for one class of disinfection byproducts, but it does reveal that exposure pathways in addition to drinking, and is a great discovery to build upon with follow-up studies.

What Can Individuals Do To Reduce Their Exposure To Disinfection Byproducts?

To be clear, the discovery of DBP exposure through showering does NOT mean that you should be afraid of showering, rather it's a piece of information that may be considered in any changes to the regulation. As frustrating as it may be to people "looking for answers," the reality is... good science is a slow process... and modifications to regulations are often even slower! While regulatory agencies and municipalities are taking steps toward reducing DBPs in water (by pre-oxidizing or filtering out organic precursors), the most effective way for consumers to reduce their exposure today is by filtering their water at the point of use, and/or by flushing stagnant water out of the pipes by letting it run for a few minutes before using it.

Sources:

- https://www.epa.gov/ (and sources therein) Accessed on 12/25/2015

- https://www.cdc.gov/safewater/publications_pages/thm.pdf

- Backer, LC, et al., 2000

- Richardson et al., 2007

Other Great Articles From Water Smarts Magazine: